We woke up to the first snowfall in Vermont. Not a big deal, just wet snow, a little ice, and the usual white coating of trees. Snow, even this little bit, makes the world quieter. I like these early snowfalls because the wood stove hums along, I have all-wheel drive and an excellent pair of boots, and I own a generator.

While wallowing in my good fortune, I began to think about New England winter storms, especially on the coast and specifically on the Vineyard. Even though Marshall and I have spent a fair amount of time rummaging in the island’s past, we hadn’t really thought much about storms and definitely not winter ones. Dipping back in time, on December 1, 1898, an epic storm that lasted for two days enveloped New England. It is described in the Vineyard Gazette as follows:

Sunday was the most eventful day that the town has known for 40 years. From early morning until late at night the water about the port was strewn with wreckage, and vessels were constantly driven ashore, many of them to be dashed to pieces.

It is known that at least ten men have perished, and it is very probable that as many more have lost their lives.

Twenty-one schooners, nearly all heavily laden, and one barkentine are ashore; four schooners now lying at anchor are totally dismasted; two others were sunk, and one bark is resting at the bottom, entirely submerged. Many other vessels were battered and partially stripped of their rigging.

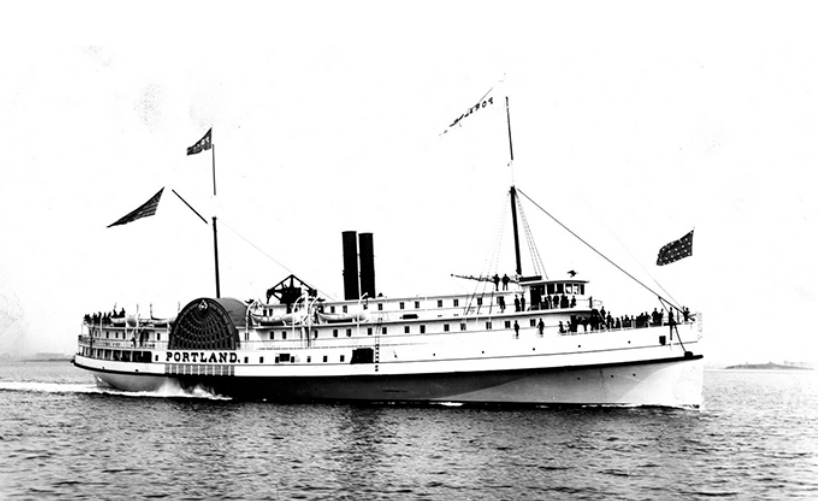

The death toll along the coast was significant, including the sinking of the steamship Portland bound from Portland to Norfolk with all 160 hands gone. The Portland's exact location was unknown until 2001. The schooner Island City ran ashore in Cottage City and all hands perished. The Gazette posts a list of all the vessels lost and often the names of the crew lost with them and includes damage sustained ashore.

The windmills and towers on the premises of Dr. T.J. Walker, Capt. Chas. W. Fisher, and James E. Chadwick were blown over, and the Russell mill at Tower Hill lost most of its vanes. The engine house of the M.V. Railroad was completely wrecked, the cupola blown from the depot building, a large balm of Gilead tree near the Richard L. Pease estate was uprooted, falling across Main street, the roof was blown from the barn of Henry Smith at the Swimming Place, and a miscellaneous amount of damage done in all parts of the village.

There is a matter-of-factness in the newspaper’s narratives. Vessels are lost, men are drowned, property is damaged beyond repair, and yet there are moments of pride and advice:

Vineyard Haven should be proud of her Seaman’s Bethel and her local W.C.T.U, as well as of all those who nobly aided.

A life saving station at East Chop and another at Chappaquiddick Bend, if established, will be the means of saving many lives some day, which will surely be lost if the stations are not soon established.

The fine catboat Thelma, Horace Hillman, master, made a New Bedford trip on Saturday with a load of fish, arriving at that port at 7.30 in the evening, before the gale got to its height. The Thelma returned to Edgartown Monday, leaving N.B. at 3.45 p.m., and making the run, via Robinson’s Hole, in less than four hours. The crew on the trip with Capt. Hillman were Sylvanus Norton, Franklin E. Fisher and Walter Hillman.

Note the underlying comment on how fast she made her passage. It should also be noted that Robinson’s Hole can be dicey as it is a passage between Buzzard’s Bay and Vineyard Sound, but the fine catboat Thelma managed the whole of it in short order.

What about everyone else on these islands operating without the benefit of electricity or good boots or freezers or phones? The Martha’s Vineyard of today is a far cry from the 1929 Vineyard of Isabel and Emily, the heroines of our new book The Washashore, and even further from the disaster of 1898. The isolation and the dependence on the sea set the island apart from the mainland more so then than now.

I often wonder what it must have been like to live on the Vineyard back then. To experience a blizzard at sea, to be washed ashore, to watch anxiously to see what was destroyed and who would not come back. I would like to listen to those stories told with embellishment where moments of heroism are admired and moments of cowardice vilified—all without the benefit of a vast and instant audience that weighs in on every comment, whether they know anything about the topic or not.

This is a story that resonants because the main characters are known to you, they are your neighbors and friends. For the most part, they have lived there for a “time” as my grandmother would say (translation = generations). The conversations are anchored in the context of place, one that is dependent on and subject to the mercurial and often terrifying whims of the sea. The sea, no matter who you are, is humbling.

To return to the first snowfall—the hemlocks on my hill are covered in snow, the woods are still, and the birds are at the feeder. It is a good place to be, out of the wind and snow, while we wait for spring and maple syrup season.

-Bird Jones