Humans have been celebrating New Year's in various ways since Babylonia. The Babylonian celebration Akitu commemorates the victory of Marduk the sky god over the evil Tiamat the goddess of the sea. It also has a lot to do with barley production and crop planting, which occurs in the Spring. The Babylonians were thought to be the first to make New Year’s resolutions, promises to pay their debts, return the stuff they borrowed, as well as continued loyalty to their king. It was generally considered that if a person held to their resolutions then the Gods would favor them.

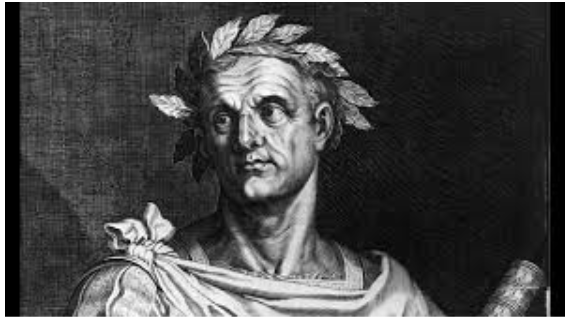

Julius Caesar fiddled around with time and the number of days in a year to create the Julian Calendar—a solar calendar with 365 days. He then proclaimed January 1 as the beginning of the new year and named the month after the God Janus of the two faces, one to look back to the past and one that looked ahead. The Romans celebrated with raucous parties, exchanging gifts, and decorating their homes.

Fast forward to 1907 and the famous ball drop in Times Square. The idea came from Adolph Ochs, the owner of the NY Times. The original ball was made of wood and iron, designed by Artkraft Straus, and lit with 100 lights. The concept grew out of maritime time balls, used to set ships' clocks, and subsequently morphed into the tradition we have today. A time ball was made out of wood and dropped from a mast set on shore at a specific time so the ships could set their chronometers, essential in maintaining their ability to correctly determine longitude. (For more on sea clocks and longitude, see our 2019 book Hold Fast.)

There are other interesting drops on New Years: Bethlehem PA drops a giant yellow marshmallow Peep—4.5 feet tall and weighing as much as 85 pounds. Tallapoosa Georgia hosts a possum drop. The town, once known as Possum Snout, features a taxidermied possum named Spencer suspended in a glass ball and decorated with Christmas lights. Spencer is kept at ground level until the required hour and then whisked to the top of the tallest building and slowly lowered to commemorate the New Year. The possum is named after a prominent 19th century business man, Ralph Spencer, who contributed to the growth of Possum Snout.

Another option is the shrimp drop on Amelia Island, Florida, in which a giant lighted shrimp descends to the joy of all in attendance. Most of these drops (and there are many more) are associated with food trucks, music, kids’ rides, and all manner of entertainment.

What about all those resolutions? The ancients made bargains with Gods and Government. For the most part, we moderns make bargains with ourselves to eat more green food or walk ten miles a day or quit smoking or lose ten pounds or just about anything you can think of. But resolutions in general are non-binding, so the vast majority fall by the wayside. The stats are not encouraging. About 38.5% of the American population sets a New Year’s resolution and only about 9% actually achieve it. Most folks give up by mid February.

But what if we shifted to intention rather than resolution? Intentions are broad and value-based. They are not particularly quantifiable and they recognize that change is an on-going process. Intentions often come in the language of growth over time—becoming kinder, more compassionate, more observant. Intentions are fluid and imply possibility while resolutions focus on what is wrong with concrete outcomes, often a recipe for failure.

Regardless of what you drop, possum, Peep, or shrimp, and what resolutions you make or intentions you set, the New Year is a moment of hope for a brighter year ahead, as it has been for 4,000 years. Unlike Janus, we have only one face to turn toward the future, however mysterious and fragile it may be, and therein lies the wonderful surprise.

Be well, all, and may this year be a good one.

-Bird Jones